OptionMetrics is now 25 years old! In celebration of the event, I was asked to comment on which market-related event most influenced me since the company’s founding in 1999. 25 years is a long time, and most of the significant events since then were related to geopolitical or economic shocks: 09/11, the Gulf War, the 2008 crash, the twin wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, the Pandemic, the rise of the internet and social media — the list goes on and on. There were also developments confined to financial markets: the dot-com boom and bust, the equity rally that is now in its 14th year, multi-year quantitative easing and near 0% interest rates, the rise of high speed and algorithmic trading, and the usual variety of trading scandals and bad behavior (Enron, Madoff, Archegos, etc.). For most people in finance, picking just one usually comes down to which affected them most personally.

For me, the choice is simple, and it’s not even close: April 20, 2020.

For those of you who don’t remember, that was the day when one of the most successful futures contracts of all time, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil, settled on the day before expiration at a negative $37.63, an unprecedented event in the long history of futures trading.[1] No major exchange traded physically delivered contract had ever done that before in the 150 year history of futures trading, and it did so in a spectacularly volatile and hyperkinetic fashion. The front month May contract settled down $55.90 on the day, with a range of $55.48, almost three times the previous day’s settlement alone.

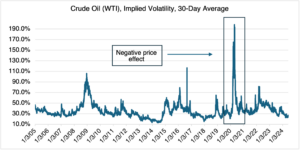

To put that level of volatility into context, that was the largest daily price change and range, in dollar value or percentage terms, since crude oil started trading on the NYMEX in 1983. Implied volatility reached 198.3% a few days later, the highest reading ever recorded for crude oil and 5.5 times its long term average, 65 volatility points higher than its close at the end of March. Even meme stock implied volatility rarely approaches that level of chaos. Most of the sell off took place just 90 minutes before the close. Below are the unlikely-looking charts:

Source: OptionMetrics

Source: OptionMetrics

How did the May contract dive into negative territory in just 90 minutes? As in almost all extreme events, no one single factor was solely to blame. Rather, a confluence of factors were responsible, some commonplace and some unique to the situation and time period.

The global pandemic had started in earnest only a few months before, subjecting all financial markets to almost unprecedented volatility. With the world locked down, and supply chains interrupted, economic activity was slowing to a standstill. As was the case with other commodities, crude oil had been under pressure since February 2020 due to massive pandemic-related oversupply and poor demand. Existing and plentiful crude supplies had to find a home somewhere, and storage quickly filled up and then became unavailable. Unlike natural gas or gold or other storage-based commodities, crude oil storage is limited and meant to be temporary. “God stores it for free” is a common expression in the industry. Since crude oil is only valuable in its refined form (gasoline, heating oil, etc.), the incentive is to refine it quickly and get it to market.

Due to the fact that each futures contract has an immutable expiration date, front month contracts tend to get increasingly volatile as expiration approaches. Simply, time was running out for all those who still owned contracts. Open interest in the May contract going into April 20th was at an historically high 105,903. At the same time, prices were coming under extreme pressure, closing under critical $20 support and in 18-year low ground.

The situation was clearly explosive. At the time, none of this was secret information and was well understood by all of those involved. By the end of the trading day, and after the wild rush for the exits precipitated by the wild price action, May open interest had declined to a paltry 15,702 contracts. The motivation of those remaining in the contract so late in the expiration cycle, given the historically dire situation, is questionable.

Practical and logistical issues resulting from the pandemic also played a role. Trading rooms were empty, and the usual market participants were either trading from home or absent. Senior management, compliance, and back office managers were also missing or difficult to reach. When crude oil made new life-of-trading lows just above $4.00 a little after 1p.m., the CME announced that negative prices were indeed allowable under exchange rules, despite the fact that a low price limit of $0.01 was still posted on the CME website. The announcement acted as a further impetus for those seeking to squeeze remaining contract owners by driving the contract into negative territory. Indeed, it had never occurred to most traders that negative prices were even possible, and it’s doubtful that most were aware of the exchange’s announcement. Under normal circumstances, senior management or on-site back office or compliance staff would have weighed in and restricted trading until the situation was clarified. Instead, communication was slow to non-existent because no one was around, and the market was free to implode.

Should the exchange have allowed crude prices to go negative in the first place? This is an interesting question, and has implications that extend beyond just futures markets.

On one hand, a market’s primary function is to provide price discovery. The outcome, however, seemingly irrational, is immaterial; as long as prices have been determined through legal means, they should be free to vary and settle as conditions merit. The exchange should not be picking winners and losers; market intervention to alter prices or influence trading will necessarily corrupt the price discovery function and lead to inefficiency. And besides, negative prices in other commodities, notably power and certain natural gas regional indexes, have occurred without deleterious long term effects.

On the other hand, the less doctrinaire point out that crude oil is a major commodity and essential to the workings of the global economy. WTI futures are not a small industrial commodity or niche product, but rather are at the center of a global pricing and physical settlement network that is essential to the workings of the global economy. Therefore, the exchanges must maintain their long term viability and legitimacy, a place where hedgers and speculators can transact every day in an orderly and fair market. Negative prices needlessly tarnish their reputation and validity, or so this side of the argument concludes.

It would be a mistake to shrug off the events of April 20, 2020 as a one off anomaly, the product of a hyperventilated market and a unique set of circumstances. The frenetic price action all crammed into an hour and a half, and the negative settlement, points out that indeed anything can happen in futures markets, and often does. Unlikely events with disproportionate impact occur with higher frequency than standard models predict; negative prices were just the latest example of this phenomenon. Excluding such events as outliers, or underestimating their probability, from standard risk management analysis can often lead to disaster. Unfortunately, all that is required is a failure of imagination.

[1] Certain natural gas and power regional indexes have traded at negative prices during periods of extreme supply/demand imbalance. Interestingly, crude oil prices were very close to negative twice before, but not in exchange traded physically delivered commodity futures: $0.05 cents, in 1861, when oil production first began in Pennsylvania, and $0.11 cents at the start of the Great Depression in 1931.